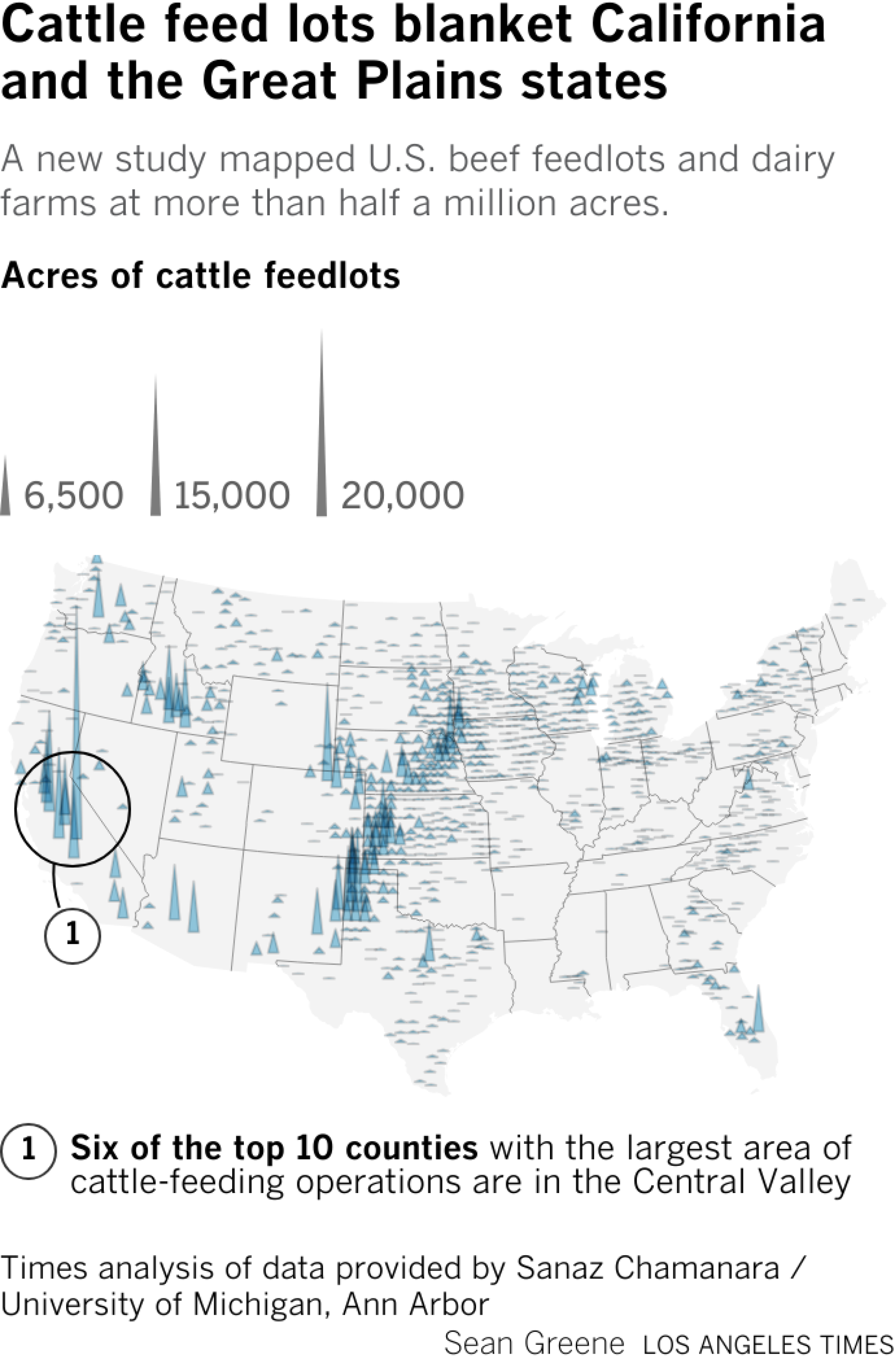

In a first, researchers have identified the nation’s roughly 8,700 cattle feeding operations, and the map shows California has more of them than any other state.

California also has the most feedlot acreage: over 85,000 acres, or 130 square miles, the majority of it for dairy cows. Tulare County has more than any county in the country — 304 operations. Were it a state, it would would rank No. 8, researchers at the University of Michigan and UC Santa Barbara found.

Until now, there has been no national database of animal feeding operations. The federal government doesn’t keep one, and states tend to keep what information they have confidential.

The researchers say their data will allow local governments and non-governmental organizations to set targeted environmental, health and economic policies for their regions.

“It’s really awesome research,” said Andrew deCoriolis, the director of FarmFoward, an anti-industrial agriculture group. “This is by far the most comprehensive research I’ve seen, both in the map … and the quantification of the number of operations.”

They also mapped the geography of hog raising. The U.S. is the world’s second-largest livestock producer (behind China) — and most of the animals are raised in confined feeding operations: 70% of cattle and 98% of hogs.

The facilities pack many animals into relatively small areas where they are fed energy-dense diets and raised for milk or meat before they are eventually slaughtered.

In California the average dairy operation is 1,300 animals, but they range from a few hundred cows in the north coast, to more than 10,000 in the San Joaquin Valley.

For decades, such operations have been associated with degraded air and water quality. There is often little vegetation and animals kick up dirt and dried manure with their hooves when they move. Other research has found the industry workforce is often underinsured and economically disadvantaged. More than 50% of the nation’s dairy workers may be undocumented.

The lack of precise location data has meant that local governments, academics and nonprofit organizations have struggled to document the effects of these facilities on the environment and community health.

So the researchers decided to build a database and map combining existing data sets — national, regional, business and crowd-sourced — that they cross-referenced with Google Earth. Then they scoured satellite imagery for more than two years, eventually pinpointing 15,726 cattle and hog feeding lots and their extent. The collective footprint exceeded 658,500 acres, or 1,000 sq. miles, slightly larger than Rhode Island.

The study was published Tuesday in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.

Seeing the amount of land dedicated to this use is important “when you’re thinking about how this affects communities living nearby, when you start to ask questions about water pollution, the size of the facility, questions about other health impacts,” said Joshua Newell, a geographer at the University of Michigan’s School for Environment and Sustainability.

Once the researchers located the feed lots, they looked at local air quality and economic data, and found the operations are associated with degraded air quality, and the more land devoted to cattle and hog farms in a given census tract, the lower the social and economic well-being of people living nearby. A look at health-insurance coverage rates, for instance, shows they significantly drop in areas near cattle feeding operations.

Anja Raudabaugh, CEO of Western United Dairies — the state’s largest dairy trade group — took issue with the study, and said the environmental and economic data were incorrect.

“The researchers either don’t know, or failed to inquire, with the EPA or the local regulating air quality authorities about existing guardrails” on air pollution, she said.

She pointed out there are several other causes of or contributors to air pollution in the San Joaquin Valley, including Interstate 5 and Highway 99, as well as “our significant and growing human population and geography that traps pollution in the valley.”

Newell responded that the analysis compared similar nearby tracts that are not right next to feeding operations — so other pollution sources were accounted for.

Last week, a federal court ruled animal feeding operations are exempt from reporting air emissions and dangerous “pollutants” to local and state officials.

Raudabaugh also took issue with authors’ claims about environmental justice, which she said were widely disputed in other research and analyses.

“We’ve discussed the real struggle of rural healthcare during recent viral outbreaks and how difficult it can be to service our communities,” she said, noting research about H5N1 bird flu and the vulnerability of a dairy workers to infection. “But arriving at a single outcome, a production style of agriculture, is like saying L.A. has lots of cars and therefore a high homicide rate.”

Instead, she said, “it would be nice to focus on increasing rural access to more healthcare where communities need it” instead of villainizing an industry that provides jobs and a “major local tax base.”