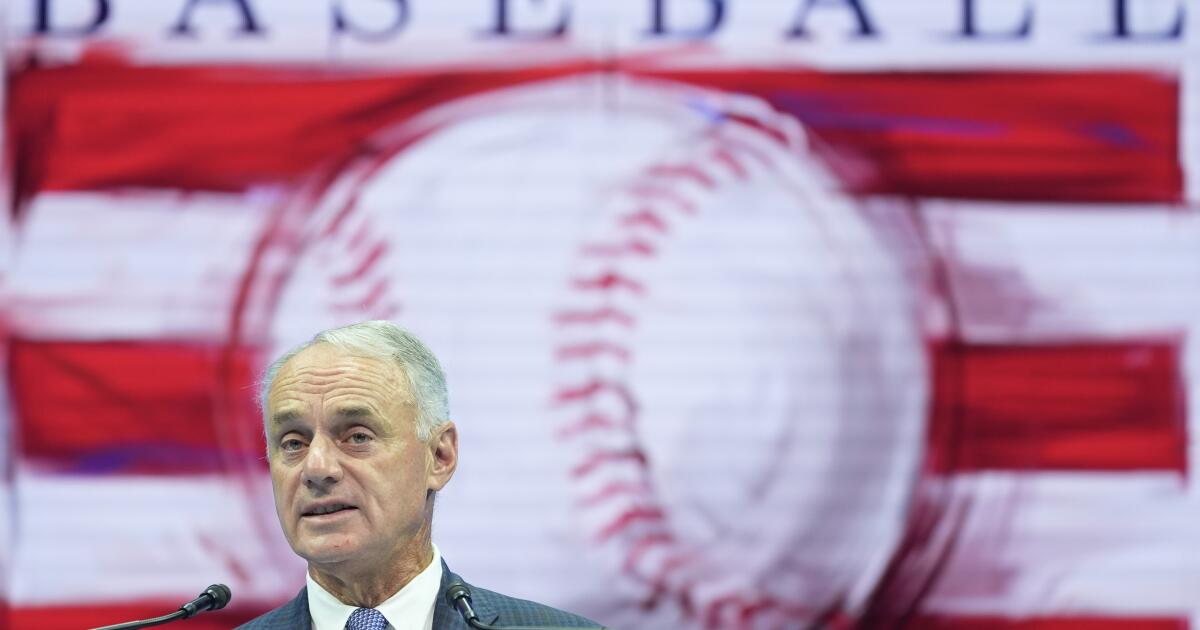

Rob Manfred normally does what many fans consider an annoyingly effective job of keeping Major League Baseball’s strategic plans out of the public square.

So maybe the MLB commissioner was caught in an unguarded moment, staring down at a diamond from the ESPN “Sunday Night Baseball” booth in the cozy confines of Williamsport, Pa., and the Little League World Series.

Or maybe his comments were calculated. Either way, he spoke freely about how expanding from the current 30 teams could create an ideal chance to reset the way teams are aligned in divisions and leagues.

Manfred was asked on air for a window into the future. Expansion, realignment, both?

“The first two topics are related, in my mind,” he replied. “I think if we expand, it provides us with an opportunity to geographically realign. I think we could save a lot of wear and tear on our players in terms of travel. And I think our postseason format would be even more appealing for entities like ESPN, because you’d be playing out of the East and out of the West.”

Taking that thinking to an extreme would put the Dodgers and Angels in a division with, say, the San Diego Padres, San Francisco Giants, Las Vegas Athletics and Seattle Mariners.

Would that collection — let’s call it the Pacific Division — be part of the American or National League? Maybe neither. Instead, geographic realignment could result in Eastern and Western Conferences similar to the NBA.

Pushback from traditionalists might be vigorous. Call them leagues, call them conferences, geographical realignment would make for some strange bedfellows.

Former MLB player and current MLB Network analyst Cameron Maybin posted on X that making sure the divisions are balanced is more important than geography.

“Manfred’s realignment talk isn’t just about moving teams around, it tilts playoff balance,” Maybin said on X. “Some divisions get watered down others overloaded and rivalries that drive October story lines we love, vanish. Baseball needs competitive integrity not manufactured shakeups.”

Yet Manfred makes a persuasive argument that grouping teams by geographic location would have its benefits.

“That 10 o’clock time slot where we sometimes get lost in Anaheim would be two West Coast teams,” he said. “Then that 10 o’clock spot that’s a problem for us becomes an opportunity for our West Coast audience. I think the owners realize there is a demand for Major League Baseball in a lot of great cities, and we have an opportunity to do something good around that expansion process.”

Manfred said in February that he’d like expansion to be approved by 2029, his last year as commissioner. MLB hasn’t expanded since the Arizona Diamondbacks and Tampa Bay (Devil) Rays were added in 1998.

Expansion teams “won’t be playing by the time I’m done, but I would like the process along and [locations] selected,” Manfred said.

Several cities are courting MLB for a franchise, and the league is reported to be leaning toward Nashville and Salt Lake City as favorites. Portland, Orlando, San Antonio and Charlotte are other possibilities.

The Times’ Bill Shaikin has pointed out that geographical realignment would be tied to schedule reform that could help kindle rivalries and encourage fans to visit opposing ballparks that are within driving distance.

The future home of the Rays is in flux, and that decision likely will precede MLB choosing expansion cities, even after the recent news that Florida developer Patrick Zalupski has agreed to pay $1.7 billion for the team.

Zalupski’s team of investors reportedly prefers to keep the Rays near Tampa. If that becomes gospel, MLB can turn its attention to choosing where new teams would call home.

And soon afterward, if Manfred’s vision comes to fruition, geographical realignment would follow, and the Southern California Freeway Series could become just another series between divisional rivals.