As California turns to satellite imagery, remote cameras watched by AI and heat detection sensors placed throughout wildlands to detect fires earlier, one Orange County group is keeping it old-school.

Whenever the National Weather Service issues a red flag warning, a sign that dangerous fire weather is imminent, Renalynn Funtanilla swiftly sends alerts to her more than 300 volunteers’ phones and inboxes.

She wheels TVs into a conference room turned makeshift command center, sets up computers and phones around the table and dispatches volunteers to dozens of trailheads and roadways in Orange County’s wildland-urban interface: likely spots for the county’s next devastating fire to erupt.

The volunteers — sporting bright yellow vests and navy blue hats with an “Orange County Fire Watch” emblem — slap large fire watch magnets to the sides of their vehicles, grab some binoculars and start to watch.

Amid California’s coastal sage scrub and chaparral ecosystems that are plagued with frequent fast-moving fires, preventing ignitions and stamping out fires before they become unmanageable is the name of the game.

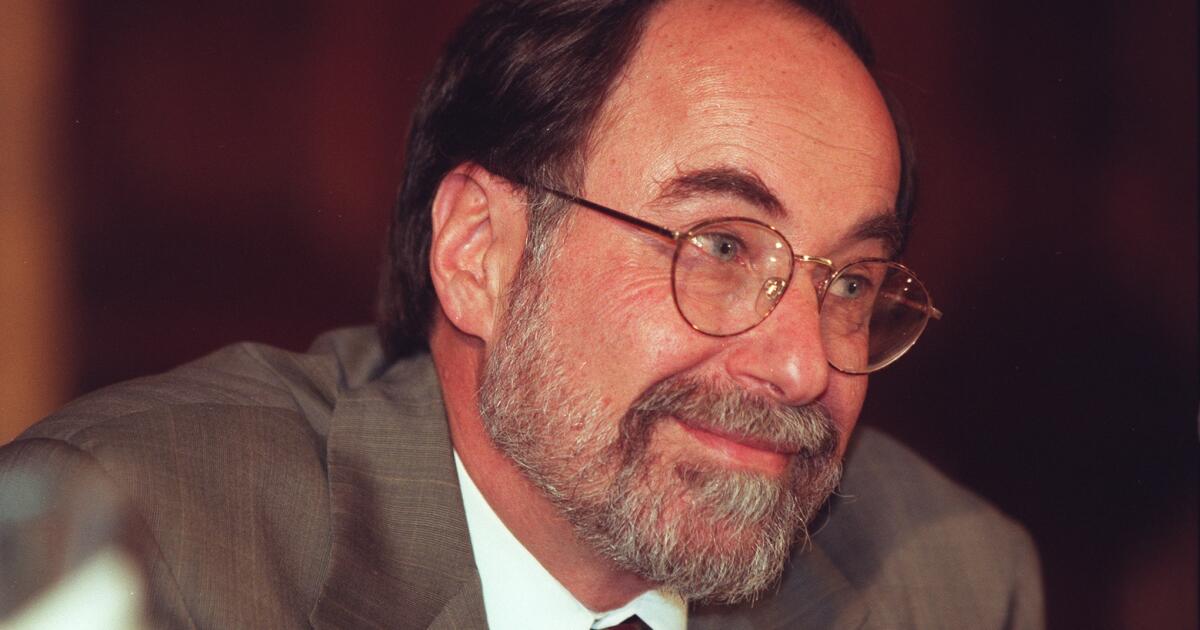

Orange County Fire Watch is betting on good Samaritans like Renalynn Funtanilla teaching the public how to prevent ignitions and keeping an eye out for potential culprits.

(Juliana Yamada / Los Angeles Times)

To do it, Orange County Fire Watch is betting on good Samaritans teaching the public how to prevent ignitions and keeping an eye out for potential culprits, from overheating e-bikes to arsonists. (In Orange County, human-operated equipment has historically been responsible for about 34% of wildfires documented by the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, while arsonists have started about 15%.)

Despite the program’s simplicity, fire experts say this system might be one of our best shots at stifling coastal California’s wildfire problem.

“When you have so-called ‘red flag days,’ that is the time to put the effort into monitoring for ignitions,” said Alexandra Syphard, who studies fire in chaparral ecosystems and causes of ignitions. “The fact that you have these volunteers doing that — it is exactly what I would recommend.”

The modern-day tale of fire in California often goes something like this: Through centuries of fire suppression, the state’s wildlands have built up a dangerous level of thick, flammable vegetation, requiring us to introduce more frequent, less intense controlled burns and forest thinning to limit the severity of major fires.

While true for the Sierra Nevadas, much of coastal California has the opposite problem. Despite the state’s best efforts to suppress fire, the number of ignitions has become increasingly frequent in the region as Californians continued to build into the wildlands and create more opportunities for sparks.

Hundreds of years ago, lightning started virtually every fire in the coastal Southern California. It now accounts for fewer than 5%, with humans responsible for the rest.

These blazes take off in part because native plants in the chaparral and sage scrub ecosystems are getting choked out by such frequent fire. Fast-growing and flammable invasive brush has been more than happy to take their spot.

During red flag days, where dry conditions give fire an optimal fuel and intense winds can transport embers miles away, controlling vicious blazes becomes incredibly difficult. Attempts to contain the blaze are often quickly thwarted by new spot fires caused by burning embers.

Once a fire starts devouring homes — an extremely dense and powerful fuel source for fires — it becomes borderline impossible for fire crews to contain.

In these conditions, “there is not a lot that can be done,” said Jeff Shelton, a California wildfire behavior consultant.

So, many experts argue preventing disaster requires stopping fires before they start — or catching them in the earliest phases. In the worst conditions, fires can grow exponentially, meaning a nascent fire going unnoticed for just a few minutes could mean the difference between a close call and the loss of homes and lives.

Hikers Tom McDonnell, of Irvine, left, and Roxanne Bradley, of Westminster, hike a scenic trail at Saddleback Wilderness.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

All of Orange County Fire Watch’s sentinels started as volunteers with the county parks or the Irvine Ranch Conservancy, which boast pools of 1,200 and 500 volunteers, respectively. That existing network of community service-focused nature lovers has helped Orange County Fire Watch become one of the largest programs of its kind in California.

To earn their coveted hats and yellow vests, each volunteer goes through first aid and public engagement training, followed by a four-hour crash course covering fire behavior, common dangerous and suspicious activities and local emergency response.

It gives them everything they need to quickly and confidently identify fires, discern their exact location and effectively alert the Orange County Fire Authority (which gives the program its full blessings).

For Phil Sallaway, it’s a way to do his part in addressing a problem that can often feel insurmountable.

“It contributes to the community in a very positive way,” he said. “I’m retired, so I didn’t want to just sit around home or be that guy in the coffee shop just drinking coffee and complaining,” he joked.

Throughout Orange County Fire Watch’s ten years serving the region, there’s been no shortage of high-tech attempts to address the problem.

In 2023, Cal Fire partnered with UC San Diego to bring artificial intelligence to the university’s more than 1,100 remote cameras strategically placed throughout the state to monitor for fires. In 2024, it detected over 1,600 fires, beating 911 calls nearly four out of 10 times.

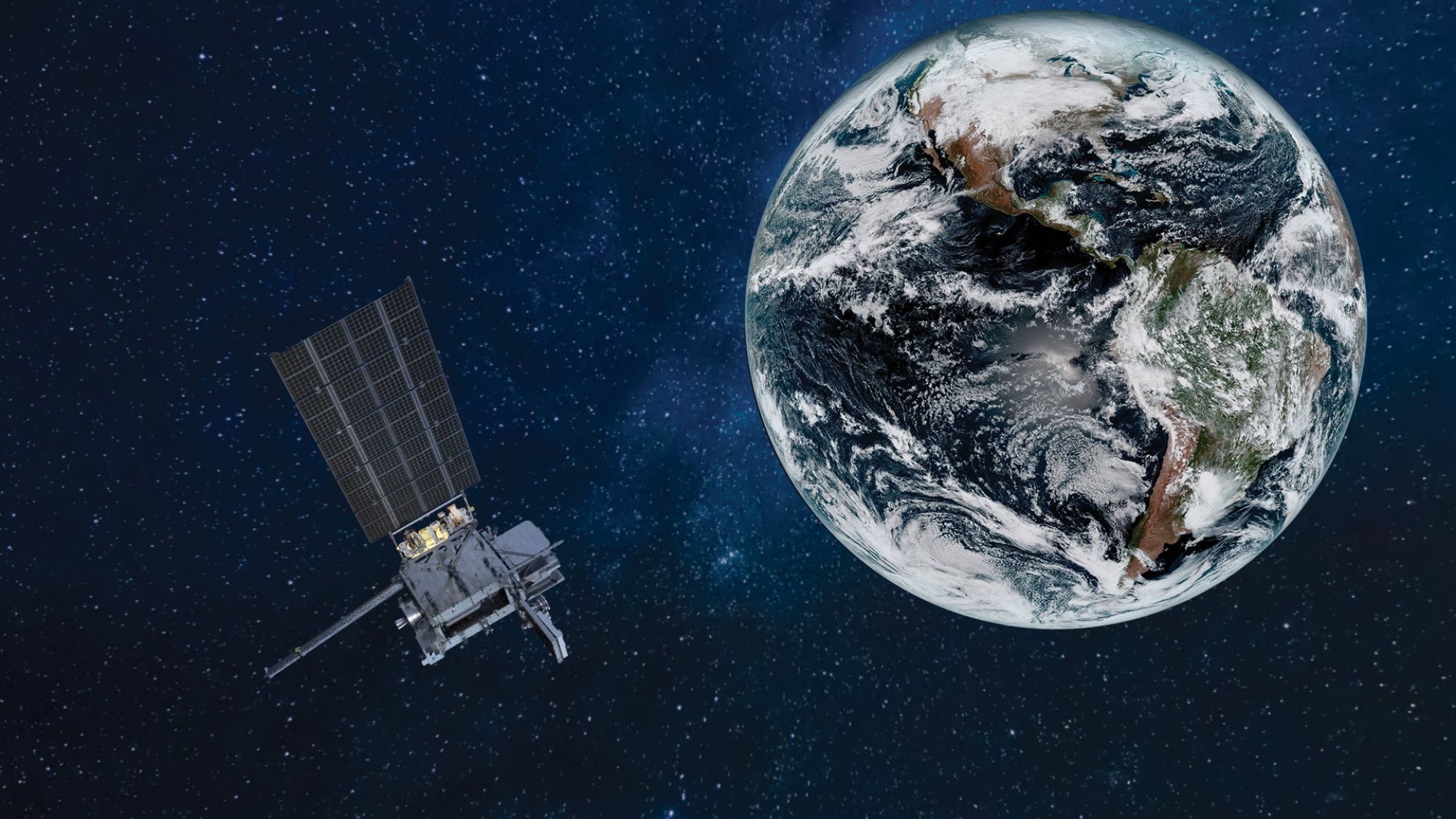

NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration launched the latest of its GOES satellites in 2024, which scan the Earth every 10 minutes for fires and other extreme weather events. In July, the Google- and Cal Fire-backed Earth Fire Alliance unveiled the first images from a prototype satellite for its FireSat constellation that will scan fire-prone regions every 20 minutes with significantly better resolution.

NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s GOES satellites scan the Earth every 10 minutes for fires and other extreme weather events.

(NOAA / Lockheed Martin)

The Irvine Ranch Conservancy, which houses the fire watch program, has even partnered with a high school student who designed a network of sensors capable of detecting the heat and smoke of new fire starts.

But both cameras and satellites lack one key piece of Orange County Fire Watch’s mission: ignition prevention.

The volunteers’ typical two-hour shifts also entail telling hikers not to light a cigarette on trail, flagging down cars accidentally sparking on the road and, hopefully, deterring arsonists.

Computers, sensors and AI “can’t talk to the public and say, ‘Hey, did you know about these red flag warning conditions?’” said Funtanilla, program coordinator for Orange County Fire Watch. “There’s definitely value to that human touch of having a person stationed with this yellow vest that someone from the public can actually ask questions.”

Orange County Fire Watch volunteer Phil Sallaway holds binoculars during a mock deployment at Ridge Park.

(Juliana Yamada / Los Angeles Times)

Yet, measuring the success of fire watch programs is not easy, Syphard said. Researchers could start by counting the number of potential ignitions avoided — like when an Orange County Fire Watch volunteer caught a car with a damaged wheel rim creating sparks on the road — but that wouldn’t account for the effect of deterrence.

Eventually, researchers could look at Orange County Fire Watch’s footprint and see if the total number of ignitions declined when the group was activated (while also accounting for all the other factors influencing ignitions), but such a study has yet to be done.

Regardless, fire experts see the approach as a cost-effective and promising way to address coastal California’s fire doom spiral by cutting the cycle off at its start.

“This type of program should be scaled up at the same time that the technology is scaled up,” Shelton said. “I would define it as indispensable.”