“This isn’t football. It’s something else and it makes my blood boil.”

Those words in 2020 from then Barcelona boss Quique Setien about Getafe’s style of play came as no surprise to their manager Jose Bordalas.

He has been accused of being a merchant of negativity throughout his managerial career, a coach whose football suffocates rather than inspires.

“Normal people don’t want to watch football like that,” Xavi once commented after his Barcelona side were frustrated by Getafe’s intensity.

Athletic forward Inaki Williams also called out Bordalas after a stormy night in Bilbao, while other managers – from Mallorca’s Jagoba Arrasate to Marcelino at Villarreal – have complained of time-wasting, dark arts and tactical cynicism.

The fact so many high-profile figures rail against Bordalas is proof, though, of his impact. Under his command, Getafe have been inconvenient, awkward and impossible to ignore.

The 61-year-old Spaniard is in his second spell with the Madrid club – returning in April 2023 after a year away with Valencia – having previously spent five successful seasons there.

You won’t hear too many complimentary voices about him from the Barcelona camp when they meet on Sunday but, despite all the ‘anti-football’ criticisms, his record speaks for itself.

Bordalas boasts the third-highest number of wins in Spanish football history for a manager across the top three divisions.

And he has guided Getafe into European football despite a wage bill consistently in the bottom third of La Liga and very little squad investment, despite bringing in 83m euros (£72m) in player sales.

This is not the resume of a firefighter clinging to survival. It is one of a coach who has repeatedly made the improbable routine.

Suffocated by demands – but players enjoy best moments

Football in Spain has long been torn between two extremes: the positional game and possession-heavy ideals descended from Johan Cruyff, and the pragmatists who prioritise structure, intensity and results.

Bordalas stands unapologetically in the latter camp but was inspired by the former.

It is simply that he has not been given the chance to put it into practice, because the clubs he has managed in the three tiers of Spanish football have not had the players to perform such football.

For aesthetes, his direct and uncompromising brand of football is unwatchable. For his players and fans, it is irresistible.

Beyond the caricature, Bordalas’ methods are rooted in structure and detail.

Training sessions can last three hours, double the usual length. Players are weighed every morning and those who return overweight after holidays are forced to train with extra kilograms strapped to their bodies.

He once challenged his players to kick a ball far enough to reach a local Madrid motorway, offering 500 euros (£432) and a starting place to whoever succeeded.

At former club Alcorcon, he set a similar test: try to head the ball out of the stadium. It is the reinforcement of his mantra – effort, competitiveness and always pushing limits.

Players often admit to feeling suffocated by his demands – and yet many confess they experienced the best football of their careers under him.

Juan Cala, who played at Getafe between 2015 and 2018, said: “He made me mad, like a father does… but he made me live the best moment of my career.”

Even before it became fashionable, Bordalas spotted three essentials: high pressure, organised defence, and a physical aptitude in the players that permits them to cover a lot of space on the field.

He demands a high, aggressive press that forces opponents to go long, as well as compact defensive lines and immediate transitions. There is no tolerance for sterile possession.

The numbers back it up. Getafe consistently rank among the teams who defend furthest from their goal, catch teams offside the most times and commit the most fouls.

The result? They allow the fewest shots on target. The sacrifice of aesthetics is the price of security.

Most recently, Bordalas has added an AI tool to his armoury, technology he hopes can give him clues on how best to position the team with the ball, without the ball, and how to force errors.

Bordalas places a lot of emphasis on improvisation and spots solutions where others see obstacles.

Take Christantus Uche. Signed as a midfielder from Ceuta by Getafe in summer 2024 for 500,000 euros (£430,000), he was reinvented as a striker to help solve a squad shortage.

The Nigerian scored on his debut and, after 33 games, four goals and six assists, he was sold to Crystal Palace for £17m as a forward.

Critics call his approach reductive. Bordalas calls it realistic.

“I’d love to control the ball more,” he said. “I’m a lover of good football, but you have to adapt to the players you have.”

That adaptability has allowed him to thrive in environments where others have failed. From Hercules to Elche, Alaves to Getafe, he has consistently overachieved with squads of modest talent.

‘Facing Bordalas is like going to the dentist’

Getafe under Bordalas is a story of overachievement – but one laced with frustration.

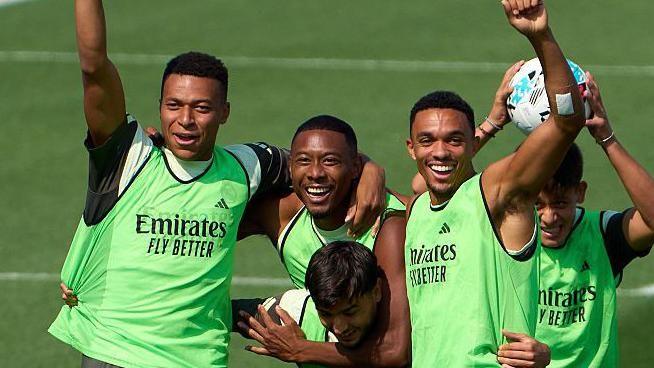

On one hand, the club have survived and in fact thrived, competing with Europe’s elite on a budget that should barely cover survival.

On the other, the realities of La Liga mean constant fire sales. He has the only squad in Spain’s top flight with six slots empty – and not by choice, because he would prefer a deeper, more competitive group.

At Getafe, he is adored. He is the leader. Fans chant his name, paint banners, and embrace his philosophy of resistance.

It is not unusual for him to be seen having a coffee with supporters in the club cafeteria – something that would never be seen at just about any other club.

It is an open secret he has helped, and continues to help, many people financially, and he often says that with so many people going through bad times his profession is a privilege.

Some of his peers, such as Atletico Madrid boss Diego Simeone, respect his methods. His best friends in football are Carlo Ancelotti and Zinedine Zidane, who understand and have learned from Bordalas.

Others may dismiss him as a spoiler, but even they know preparing to face a Bordalas team means 90 minutes of discomfort.

Former Sevilla boss Joaquin Caparros once described facing him as “like going to the dentist”.

Even his harshest critics have publicly praised Bordalas for getting such extraordinary performances from what is essentially an ordinary squad.

‘This is football, dad’ – how Bordalas became a meme

Bordalas’ own story mirrors those of his teams: a tale of survival, graft and improbable ascent.

Born in Alicante, one of 10 children, he worked summers picking melons and watermelons to be able to afford a bicycle.

These days he is keen to point out his main duties were helping a company sell their products to shops.

But football was always Bordalas’ true love. By the age of 28, injuries ended a modest playing career in the Spanish lower divisions and coaching beckoned, firstly with youth teams and then with a number of lower-league clubs across the Valencian region, starting with Alicante in 1994.

His managerial career spans 12 different clubs and countless promotions and rescues.

In 2015-16 he led Alaves into the top flight – only to be dismissed at the end of the season. Months later, Getafe called.

He joined them in the relegation places in Segunda, but ended the campaign with promotion to La Liga. Within two years, he had them playing European football.

At Valencia, owner Peter Lim did not keep him for a second year despite the team achieving their highest league finish for years and reaching the Copa del Rey final.

Perhaps his most famous phrase sums up the defiance of his career.

Before a match with Villarreal, amid a storm of criticism about his style, he said to reporters with a grin on his face: “Esto es futbol, papa [This is football, dad].”

It became a meme and a symbol of his refusal to apologise for his methods. Where others see ugliness, he sees truth.

Spanish football often defines itself through beauty: the tiki-taka inheritance of Cruyff and Pep Guardiola, the artistry of Andres Iniesta and Xavi, the elegance of possession.

But beneath that surface lies a reality. Football is not always beautiful. For every Barcelona, there is a Getafe.

Bordalas represents that other Spain – the combative, uncompromising football that endures through grit. He is a reminder that the game is broad enough for many styles and success does not always look the same.

He has never won La Liga, he has not lifted the Copa del Rey or the Champions League. But he is a manager who consistently achieves the high targets he sets for himself and his team.